Nadleh Whut’en and Stellat’en First Nations share a deep history. Our two communities were combined by the early colonial government as the Fraser Lake Indian Band. In the 1906 Barricade Treaty, promises were made to provide education to the community’s children.

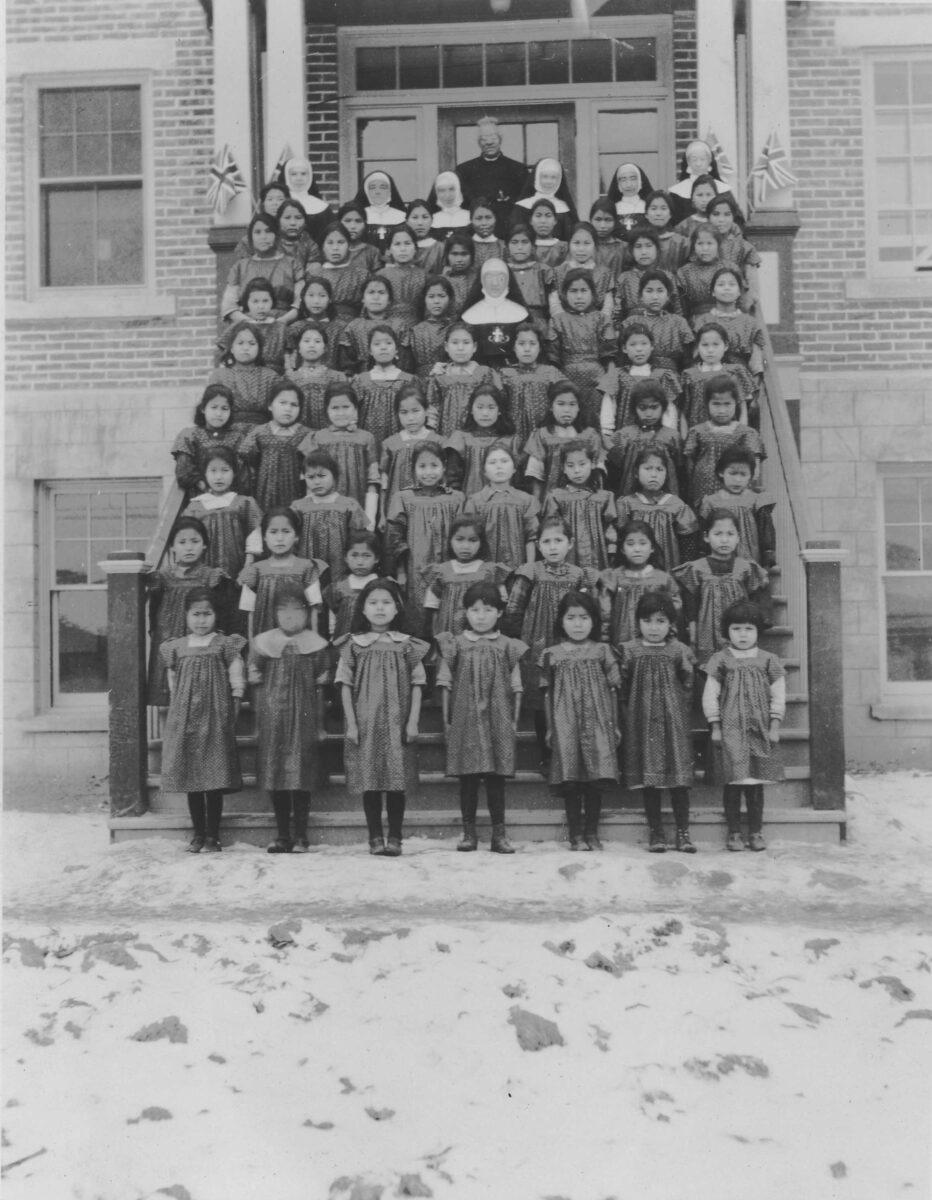

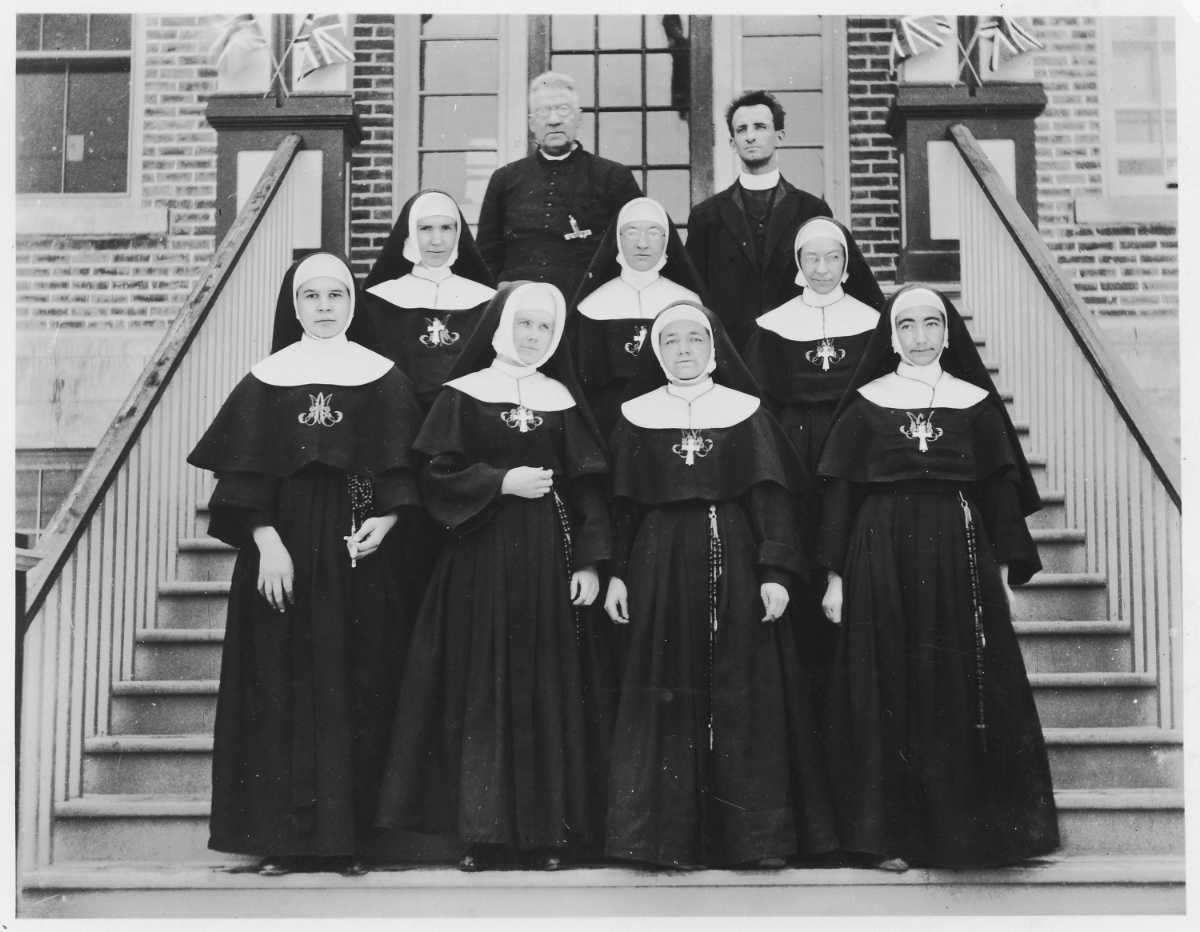

Then came the Lejac Indian Residential School (LIRS), run by the Catholic Church on behalf of the Government of Canada for over 50 years. From 1922 to 1976, Lejac attempted to assimilate and erase our peoples’ cultures, languages, and connection to the land. This colonial agenda, driven by the Crown, contradicted the spirit of the Barricade Treaty, which sought to provide education as a means to a better future.

The Nations had no say in Lejac’s operation or the treatment of our children. At one point, it was illegal for parents to challenge the residential school system by hiring lawyers or keeping their children from attending the school. Since Lejac’s closing, our communities have carried a shadow of hurt and loss caused by the school’s dark legacy.

Though the school building no longer stands, the site of the former Lejac Indian Residential School holds profound significance. It is a place of remembrance for the children who never returned home. The grounds still contain a cemetery, and considering that there are children unaccounted for in survivors’ memories, there may be unmarked graves on the premises.

Timeline

1892

Fraser Lake Indian Band

Nadleh Whut’en and Stellat’en First Nations were once one community known as the Fraser Lake Indian Band.

1906

Barricade Treaty

A significant part of their history is that the Fraser Lake Indian Band signed the Barricade Treaty, which included provisions for their children’s education.

1917-1958

National Truth and Reconciliation Commission – Documented student deaths (38)

Ownership of the land was transferred to the Nadleh in 1990, and soon later, the building was razed to the ground

1922

Construction of school

The Lejac Indian Residential School (LIRS) was run by the Catholic Church on behalf of the Government of Canada for over 50 years from 1922 to 1976. The school was meant to assimilate and erase our peoples’ culture, languages, and connection to the land, directly contradicting the intent of the Barricade Treaty to provide education to the nation’s children according to the nation’s vision of a better future. Since Lejac’s closing in 1976, our community has had a shadow of hurt and loss from the school’s impacts.

LIRS was one of 18 Indian Residential Schools in British Columbia.

1922-1976

Territory and Nation overlaps

Located on the south side of Fraser Lake, BC.

Indigenous children from 70 First Nations attended the Lejac Indian Residential School, from as far north as Tahltan and Fort Nelson, as far west as Hartley Bay, as far east as Fort George (Prince George), and as far south as Nazko (southeast of Quesnel).

1922-1976

How many students attended

Throughout the 54 years the institution was in operation, a minimum of 7,850 Indigenous children attended the Lejac Indian Residential School, including students who attended during the day, referred to as scholars.

The Truancy Section of the Indian Act, referred to in Document 5, was part of the 1920 amendment to the Indian Act, enforcing all First Nations children to attend day school or residential school. This section said the government could make anyone a truant officer, allowing them to enforce attendance and giving them the right to “enter any place where he has reason to believe there are Indian children” of school age and to arrest and convey them to school.

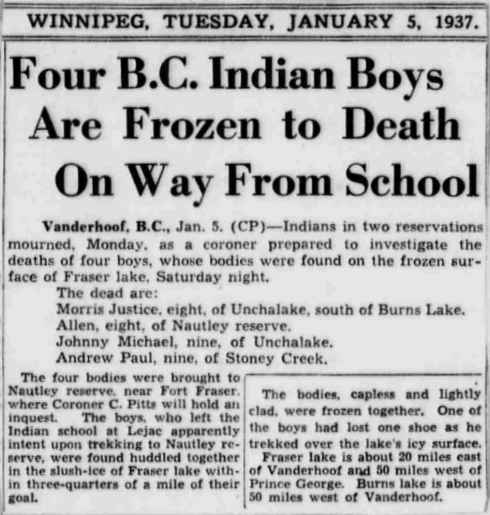

1937

Four boys running away from Lejac

On January 2, 1937, four boys—Allen Patrick, Andrew Paul, Justa Maurice, and John Michel Jack, aged seven, eight, and nine—were found dead, their bodies frozen while trying to cross Fraser Lake after running away from the nearby Lejac Residential School. The boys were found a mile from the Nautley reserve in -20 degree weather with no winter clothes. On January 1, 1937, the boys had asked to return home to see their families but were denied. Later, at supper time, a nun reported the children missing to Bishop Codert. A search party was not organized until the next day, and the boys’ bodies were found at 5 pm on Fraser Lake, less than half a mile from shore.

The Lejac deaths made national headlines and prompted an investigation from British Columbia, as well as a report ordered by the Ottawa Department of Indian Affairs.

An archival record of Indian Affairs, Indian Agent R.H. Moore’s report notes that two priests appointed to Lejac Indian Residential School from France served as disciplinarians at the school, despite having no English language proficiency and no experience with Indigenous people. R.H. Moore recommended dismissing these French priests to reduce truancy and absenteeism among students.

1965-1973

Report of horrific conditions

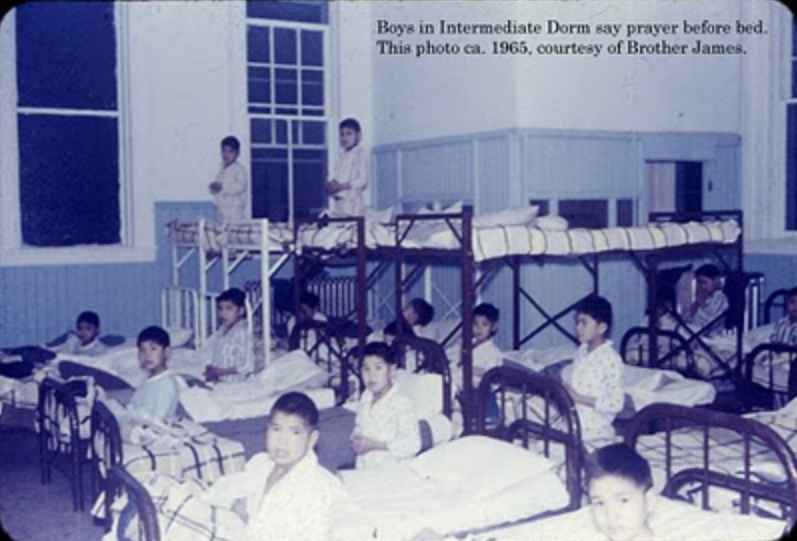

In the annual report, Principal Reverend Alex R. Simpson discussed the growing demand from communities for a day school instead of the Lejac Indian Residential School. He aimed to challenge the communities’ cultural and economic lifestyle, which revolves around the seasonal rhythms of the land rather than being entirely sedentary. Simpson also criticized parents for not enforcing discipline by allowing their children to stay home when possible. He emphasized the need for the school to expand its facilities to cater to the Stuart Lake, Babine, Stikine, and Skeena regions. The principal advocated for the expansion and stricter enforcement of mandatory attendance for children in these areas. Increasing attendance of children over the years was necessary to provide education and training, according to the principal.

1945

Lawyer W. Irvine

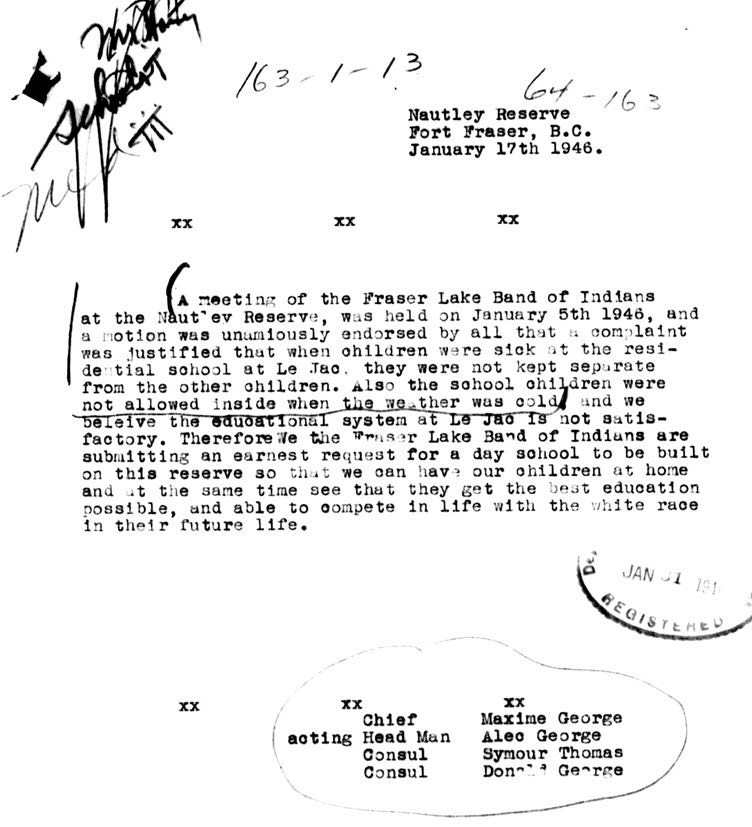

In September 14, 1945, the Fraser Lake Indian Band sent a meeting notice requesting a unanimous band vote to build a day school on the reserve instead of continuing the operation of the Lejac Indian Residential School. The letter highlighted widespread tuberculosis infection, improper care of children, lack of quarantine for sick children, and the children not being allowed inside during freezing weather. Parents were seeking the best education possible by having a school close by so they could care for their children.

1946

Principal General Report TB Epidemic

March 31, 1946, General Report Principal Reverand Alex R. Simpson documented a rampant flu epidemic in Lejac Indian Residential School. First, 65 children were in bed with the flu. Then, it progressed to the four nuns, staff, and 15 children running a fever. It was reported that children were slow to recover. Simpson reported requesting the Department of Indian Affairs for vitamins and acne medication for the children with no response. The principal noted another health matter: an X-ray survey was needed to diagnose active tuberculosis cases among school children.

1946

Headman Meeting

On January 17, 1946, lawyer Wilson wrote to the Indian commissioner regarding the concerns of local First Nations. The chiefs and leaders of the nations were worried about the conditions of children and had expressed their grievances. They were protesting against the poor care of children, which had led to the spread of tuberculosis. It was reported that children wee getting infected due to the lack of quarantine protocols. There were even claims that healthy children were being X-rayed and examined when returning home from school, only to die shortly after. Families were keeping their children home due to concerns about the time spent on manual labor and religious instruction rather than education. They argued that children were working to support the farm rather than receiving a quality education. Wilson mentioned, “The children go to school to learn to pray and milk cows.” The community believed that it is better for children to work at home with their families rather than at a residential school. Instead, the communities were requesting a day school to be built on the reserve to provide care for the children. Wilson stated that the community seeks to build a public school for Indigenous children on the same basis as schools for white children. The community only requested support in clearing land and obtaining farming machinery to improve production. Lastly, the nation requested to receive an old age pension like any other Canadian citizen, as they were only receiving $4 a month.

In January 1947, the Indian Agent wrote a letter to the department outlining the cost of converting the recreational hall into a day school. Stony Creek would complete the labour without cost and would also pay for some costs associated with accommodations for a teacher’s residence. R. Howe emphasized that the Stony Creek Band had 66 children in the community, with 30 remaining without education. Howe noted the difficulty of enforcing attendance and the necessity of a day school, especially given the community’s desire for one. Furthermore, Howe mentioned that a local teacher was interested in a future position. Howe asked for advice on salary and allowance pay for teachers. Howe urged support for the day school and a teacher, especially with the increasing community antagonism against Lejac Indian Residential School and the difficulty with attendance enforcement.

1946

Indian Agent Report Rising Unrest

On September 12, 1946, Indian Agent R. Howe reported to the Department of Mines and Resources, Indian Affairs, documenting over 100 absentee students. After the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) got involved, 70 students remained missing. There was growing disapproval of Lejac Indian Residential School from local Nations protesting the time spent doing manual labour and religious instruction. The Stony Creek Band (Saik’uz First Nation) had 40 children absent from school and they refused to send them to Lejac. R. Howe issued 15 notices to parents and urged them to enforce the truancy law to ensure school attendance. R. Howe asked for department approval to issue summons. He also strongly recommended appointing a new school inspector to B.C. to meet with First Nations and investigate complaints.

1947

New school

On January 24, 1947, Indian Agent R. Howe followed up with a letter dated December 1946, requesting that Stoney Creek build a day school. The letter outlined the requests for costs associated with materials and supplies needed for the construction. It was noted that Stoney Creek had undertaken this project without authority or advice from the Indian Affairs office, and it mentioned that labour will be provided at no cost.

Agent R. Howe pointed out that only half of the school-age children were currently attending classes at Lejac, leaving a significant portion of the community unserved. Additionally, the band had secured a teacher for the upcoming term. Howe’s letter strongly urged support for the building costs and teacher’s salary, particularly given the challenges in enforcing school attendance at Lejac.

1950s-1980s

Child welfare

An insidious result of this removal was that whole generations of First Nations children grew up without their parents. This removal of the foundational bond that children need resulted in immense and lasting trauma for Indian Residential School Survivors. Even after the last residential school closed, First Nations children continued to be targeted by the Canadian state, being removed from their families and placed in non-Indigenous foster care at rates far higher than non-Indigenous Canadians. While the initial wave of child apprehension has been dubbed the “60s Scoop,” Indigenous children continue to be taken from their families at startling rates. While only making up 7.7% of children in Canada, Indigenous children account for over half of all children in foster care.

According to Cindy Blackstock, the director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, foster care has replaced the residential school system. In fact, more Indigenous children are in foster care today than were enrolled at residential schools at the height of the system. The disconnect from families, community, and culture has serious and long-term effects. Much like Indian Residential School Survivors, children raised in foster care are more likely to suffer from trauma, mental illness, and drug abuse disorders. Children raised in foster care are also more likely to end up in prison – which has caused researchers to call this the foster care-to-prison pipeline. Indigenous peoples are extremely overrepresented among prison populations, and two-thirds of Indigenous people in prison were raised in foster care, as opposed to 1/3 of the non-Indigenous prison population. These harrowing statistics point to the continuing structural injustices being suffered by Indigenous peoples in Canada. While Indian Residential Schools themselves have caused ripples of suffering through generations of Indigenous families, the colonial attitudes, policies, laws, and practices that originally inspired the schools have continued to cause new damage to Indigenous peoples.

1965-1973

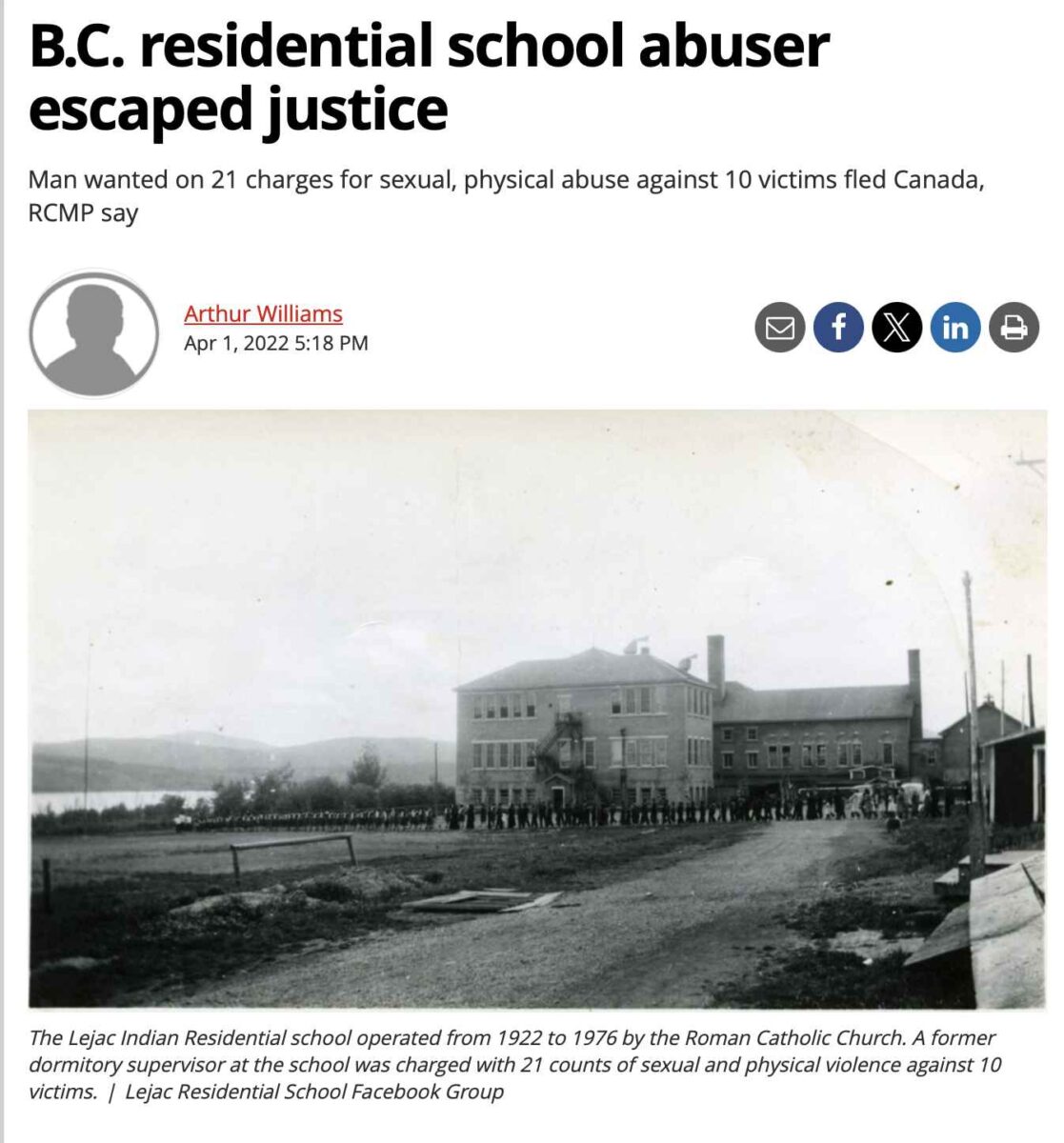

Edward Gerald Fitzgerald

In 2003, the RCMP charged Edward Gerald Fitzgerald, former boys’ dormitory supervisor, with physically and sexually assaulting 10 children at Lejac and at St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School near Williams Lake. Fitzgerald, who was 77 at the time, fled to Ireland and never faced justice for the alleged crimes.

1990

Decommissioned

The former residential school’s buildings were destroyed by the federal government in 1990.

2021

Kamloops Indian Residential School Findings

In 2021, Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc shared their preliminary survey findings of 215 unmarked graves on the site of Kamloops Indian Residential School. The findings sparked a nationwide shift in recognizing the atrocities committed in residential schools. The growing awareness has shifted the public’s awareness of the historical and ongoing trauma and impacts faced by Indigenous communities. Furthermore, the federal government has dedicated funding to addressing the legacies of the residential school system. These resources are critical to supporting community-led initiatives focused on healing, cultural revitalization, research, field investigation, commemoration and memorialization.

The Residential Schools Missing Children Community Support Fund is now funding: 136 communities for research and knowledge gathering, 118 communities for commemoration and memorialization, 83 communities for fieldwork investigation.

The findings across the country call for Canada to continue to learn and recommit to the ongoing work of reconciliation and healing.

2023

Nadleh Search

After nearly 50 years since its closure, the Lejac Residential School continues to hold significant importance due to the possibility of unmarked graves of the children who never made it home. To address this, the Chief and Council of Nadleh Whut’en have initiated a project led by the Lejac Indian Residential School Guiding Team, which includes survivors and intergenerational survivors. The goal of the project is to plan for the future of the site with a focus on healing and reconciliation. This initiative aims to honor the ancestors and seek healing for the community and other affected communities. It is an essential step in uncovering the truth, healing from the past, and showing respect for those who endured this trauma. The ongoing search is part of the community’s commitment to its people, both past and present, and contributes to continuing reconciliation efforts.

Lejac Residential School Site Search

Lejac Residential School Site Search